Fort Laramie Treaty Art Xii 34th Adult Male Women

General William T. Sherman (3rd from left) and Commissioners in council with chiefs and headmen, Fort Laramie, 1868 | |

| Signed | Apr 29 – November 6, 1868[a] |

|---|---|

| Location | Fort Laramie, Wyoming |

| Negotiators | Indian Peace Commission |

| Signatories |

|

| Ratifiers | US Senate |

| Language | English |

| Total text | |

| | |

The Treaty of Fort Laramie (likewise the Sioux Treaty of 1868 [b]) is an understanding between the United States and the Oglala, Miniconjou, and Brulé bands of Lakota people, Yanktonai Dakota and Arapaho Nation, following the failure of the first Fort Laramie treaty, signed in 1851.

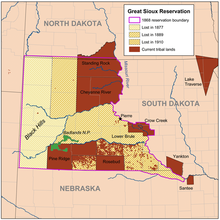

The treaty is divided into 17 manufactures. Information technology established the Great Sioux Reservation including buying of the Black Hills, and set bated additional lands equally "unceded Indian territory" in the areas of South Dakota, Wyoming, and Nebraska, and perhaps Montana.[c] Information technology established that the US regime would hold authority to punish not only white settlers who committed crimes confronting the tribes but also tribe members who committed crimes and were to be delivered to the government, rather than to face up charges in tribal courts. Information technology stipulated that the authorities would abandon forts along the Bozeman Trail and included a number of provisions designed to encourage a transition to farming and to move the tribes "closer to the white human's style of life." The treaty protected specified rights of third parties not partaking in the negotiations and finer ended Red Deject's State of war. That provision did non include the Ponca, who were not a political party to the treaty and so had no opportunity to object when the American treaty negotiators "inadvertently" broke a separate treaty with the Ponca by unlawfully selling the entirety of the Ponca Reservation to the Lakota, pursuant to Article 2 of this treaty.[3] The United States never intervened to return the Ponca land. Instead, the Lakota claimed the Ponca land equally their own and set about attacking and demanding tribute from the Ponca until 1876, when US President Ulysses S. Grant chose to resolve the situation past unilaterally ordering the Ponca removed to the Indian Territory. The removal, known as the Ponca Trail of Tears, was carried out by force the post-obit twelvemonth and resulted in over 200 deaths.

The treaty was negotiated by members of the regime-appointed Indian Peace Commission and signed between April and Nov 1868 at and near Fort Laramie, in the Wyoming Territory, with the final signatories existence Red Cloud himself and others who accompanied him. Animosities over the understanding arose quickly, with neither side fully honoring the terms. Open war again broke out in 1876, and the U.s. government unilaterally annexed native state protected under the treaty in 1877.

The treaty formed the footing of the 1980 Supreme Court case, United states of america v. Sioux Nation of Indians, in which the court ruled that tribal lands covered under the treaty had been taken illegally by the US authorities, and the tribe was owed bounty plus interest. As of 2018 this amounted to more than than $1 billion. The Sioux take refused the payment, demanding instead the return of their land.

Groundwork [edit]

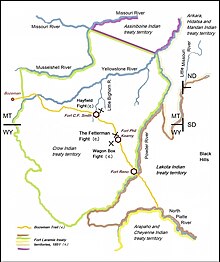

Map one. Some of the 1851 Fort Laramie territories. Later and at different times, each tribe would enter into new treaties with the United states of america. The event was an oftentimes-changing patchwork of bigger and smaller parts of the initial allocations, newly established reservations, and former tribal land turned into new US territory. The assuming outline shows the 1851 Sioux treaty surface area.

The first Treaty of Fort Laramie, signed in 1851, attempted to resolve disputes between tribes and the US Government, also as among tribes themselves, in the modern areas of Montana, Wyoming, Nebraska, and North and Southward Dakota. It fix out that the tribes would make peace among ane some other, allow for certain outside access to their lands (for activities such as travelling, surveying, and the construction of some regime outposts and roads), and that tribes would exist responsible for wrongs committed past their people. In return, the Usa Government would offer protection to the tribes, and pay an annuity of $50,000 per year.[4] [v]

No land covered by the treaty was claimed by the Usa at the time of signing. The five "corresponding territories" of the participating tribes – Sioux, Arapaho and Cheyenne, Crow, Assiniboine, Arikara, Hidatsa[d] and Mandan – were defined. Northward of the Sioux, the Arikara, Hidatsa and Mandan held a joint territory. The territory of the Crows extended westward from that of their traditional enemies[6] : 103, 105, 134–six in the Sioux tribe. The Powder River divided the two lands.[7] : 595

When the Senate reduced the annuity to 10 years from originally 50, all tribes except the Crow accepted the cut. Nonetheless, the treaty was recognized as being in force.[seven] : 594

The 1851 treaty had a number of shortcomings which contributed to the deterioration of relations, and subsequent violence over the next several years. From an inter-tribal view, the lack of any "enforcement provisions" protecting the 1851 boundaries proved a drawback for the Crow and the Arikara, Hidatsa and Mandan.[8] : 87 The federal government never kept its obligation to protect tribal resources and hunting grounds, and only fabricated a single payment toward the annuity.[4] [v] [9]

Although the federal government operated via representative democracy, the tribes did so through consensus, and although local chiefs signed the treaty equally representatives, they had limited ability to command others who themselves had non consented to the terms. This of course is impossible to confirm as the Indians had no writing and hence no fashion of recording their political philosophy[ citation needed ]. The discovery of gold in the west, and the construction of the Union Pacific Railroad, led to substantially increased travel through the area, largely outside the 1851 Sioux territory. This increasingly led to clashes betwixt the tribes, settlers, and the Us authorities, and eventually open war between the Sioux (and the Cheyenne and Arapaho refugees from the Sand Creek massacre in Colorado, 1864)[10] : 168–lxx and the whites in 1866.[iv] [5] [9]

Map two. Map showing the major battles of Red Deject's War, along with major treaty boundaries. During Red Cloud's War, the Sioux defeated the US Ground forces on the same plains on which they previously defeated the Crow. In 1868, the United states of america and the Sioux entered into negotiations regarding the western Powder River area, although neither held the treaty rights to the land.[7] : 595

None of the other tribes signing the 1851 treaty engaged in battle with the US soldiers,[11] : LVII [12] : 54 [thirteen] : 161 [xiv] : 11 and most allied the Army.[8] : 91 [12] : 127 [thirteen] : 161 [xv] : 129 With the 1851 intertribal peace soon cleaved,[16] : 572–three [17] : 226, 228 [18] : 103 [19] : 119, 125–140, 178 the Arikara, Hidatsa and Mandan called for Usa military support against raiding Sioux Indians in 1855.[12] : 106 Past summer 1862, the three tribes had abandoned all their permanent villages of earth lodges in the treaty territory south of the Missouri, which was now under Sioux control, and lived together in Like-a-Fishhook Village north of the river.[12] : 108 [20] : 408

In the mid-1850s, the western Sioux bands crossed the Pulverization River and entered the Crow treaty territory.[21] : 340 Sioux principal Cherry-red Cloud organized a state of war party against a Crow camp at the mouth of Rosebud River in 1856.[19] : 119–124 Despite the Crows fighting "... large-scale battles with invading Sioux" most present-twenty-four hours Wyola in Montana,[14] : 84 the Sioux had taken over the western Powder River expanse by 1860.[22] : 127

In 1866 the U.s.a. Department of the Interior called on tribes to negotiate safe passage through the Bozeman Trail, while the United States Section of War moved Henry B. Carrington, along with a column of 700 men into the Pulverization River Basin, sparking Red Cloud'southward War.[23] However, well-nigh of the carriage track to the city of Bozeman "crossed state guaranteed to the Crows under the 1851 treaty"[due east] "... the Sioux attacked the United states of america anyway, challenge the Yellowstone was now their land."[eight] : 89 Red Cloud'southward war "... appeared to be a swell Sioux state of war to protect their land. And it was – only the Sioux had only recently conquered this land from other tribes and now defending the territory both from other tribes"[18] : 116 and the passing through of whites.[10] : 170, note 13 [24] : 408 [25] : 46 [26] : 20 During the state of war, the Crows sided with the soldiers in the isolated garrisons.[27] : 91 [28] : 67 Crow warrior Wolf Bow urged the Army to, "Put the Sioux Indians in their ain country, and keep them from troubling us."[28] : 69

Afterward losing resolve to continue the war, following defeat in the Fetterman Fight, sustained guerrilla warfare by the Sioux, Cheyenne and Arapaho, exorbitant rates for freight through the surface area, and difficulty finding contractors to piece of work the rail lines, the United states Regime, organized the Indian Peace Commission to negotiate an finish to ongoing hostilities.[ii] [29] A peace counsel chosen by the government arrived on April 19, 1868, at Fort Laramie, in what would later become the state of Wyoming. The outcome would exist the 2d treaty of Fort Laramie Treaty, signed in 1868.[29] [thirty] : 2

Articles [edit]

The treaty was laid out in a series of 17 articles:

Article I [edit]

Map three. By right of commodity I in the 1868 treaty, the US compensated the Pawnee with annuities owed the Sioux, afterwards the Massacre Canyon boxing in Nebraska on August 5, 1873. The Pawnee received $9,000.

Article one called for the abeyance of hostilities, stating "all war between the parties to this agreement shall for always [sic] cease." If crimes were committed by "bad men" amid white settlers, the government agreed to arrest and punish the offenders, and reimburse any losses suffered by injured parties. The tribes agreed to turn over criminals among them, any "bad men among the Indians," to the government for trial and punishment, and to reimburse any losses suffered by injured parties.[31] If any Sioux committed "a wrong or depredation upon the person or property on whatever one, white, black, or Indians" the The states could pay damages taken from the annuities owed the tribes.[7] : 998 These terms finer relinquished the authority of the tribes to punish crimes committed against them by white settlers.[32] : 37

Similar provisions appeared in ix such treaties with various tribes. In practice, the "bad men among the whites" clause was seldom enforced. The first plaintiff to win a trial case on the provision did so in 2009, based on the 1868 Fort Laramie treaty.[33] : 2521

In 1873, the US exercised the right to withhold annuities and compensate for Sioux wrongs confronting anyone, including Indians. After a massacre on a moving Pawnee camp during a legal Sioux hunting trek in Nebraska,[f] [34] [35] : 53–7 [36] : 41 [37] the Sioux "were made to pay reparations for the loss of life, meat, hides, equipment, and horses stolen..."[38] : 46 The Pawnee received $9,000.[34] : 139 [39] : 154

Article II [edit]

Article two of the treaty changed the boundaries for tribal land and established the Great Sioux Reservation, to include areas of present day Southward Dakota due west of the Missouri River, including the Black Hills. This was set aside for the "absolute and undisturbed use and occupation of the Indians".[2] [31] In full, it allocated nigh 25% of the Dakota Territory equally it existed at the time.[30] : 4 It made the total tribal lands smaller, and moved them farther eastward. This was to "have away access to the prime number buffalo herds that occupied the area and encourage the Sioux to get farmers."[40] : 2

The regime agreed that no parties, other than those authorized by the treaty, would be allowed to "pass over, settle upon, or reside in the territory".[31] Co-ordinate to ane source writing on commodity two, "What remained unstated in the treaty, merely would have been obvious to Sherman and his men, is that land not placed in the reservation was to be considered United States property, and not Indian territory."[32] : 37–eight

As in 1851, the United states of america recognized most of the land northward of the Sioux reservation every bit Indian territory of the Arikara, Hidatsa and Mandan.[yard] [vii] : 594 [h] In add-on, the U.s. notwithstanding recognized the 1851 Crow merits to the Indian territory west of the Powder. The Crow and the Us came to an agreement about this expanse on May 7, 1868.[i] [7] : 1008–11 [8] : 92

With the reservation border following "the northern line of Nebraska", the Peace Commission ceded to the Sioux the petty Ponca reservation, which had already been guaranteed the Ponca in multiple treaties with the authorities.[j] [41] : 836–7 "No one has ever been able to explain" this blunder, which was yet enforced past the government, irrespective of their earlier agreements.[42] : 21

Commodity Three [edit]

Commodity three provided for allotments of up to 160 acres (65 ha) of tillable land to be set aside for farming past members of the tribes.[31] [43] : 15 By 1871, 200 farms of eighty acres (32 ha) and 200 farms of 40 acres (xvi ha) had been established including lxxx homes. By 1877, this had risen to 153 homes "fifty of which had shingle roofs and most had board floors" according to an 1876 written report past the Bureau of Indian Diplomacy.[43] : 15

Article IV [edit]

The government agreed to build a number of buildings on the reservation:

- Warehouse

- Store-room

- Agency building

- Physician residence

- Carpenter residence

- Farmer residence

- Blacksmith residence

- Miller residence

- Engineer residence

- School house

- Saw manufactory[31]

Article iv also provided for the institution of an agency on the reservation for the purpose of regime administration. In practice, five were constructed and two more than later added. These original five were composed of the Grand River Agency (Afterward Standing Rock), Cheyenne River Agency, Whetstone Agency, Crow Creek Agency, and Lower Brulé Agency. Another would subsequently exist gear up up on the White River, and once more on the North Platte River, simply would afterward be moved to as well exist on the White.[30] : v–half dozen

Articles V through X [edit]

The government agreed that the amanuensis for the Bureau of Indian Affairs shall keep his office open to complaints, which he will investigate and forward to the Commissioner. The decision of the Commissioner, subject to review by the Secretary of the Interior, "shall be binding on the parties".[31]

Article six laid out provisions for members of the tribes to take legal individual ownership of previously normally held state, up to 320 acres (130 ha) for the heads of families, and 80 acres (32 ha) for any developed who was not the head of a family.[30] : 5 [31] This state and then "may exist occupied and held in the exclusive possession of the person selecting it, and of his family unit, then long every bit he or they may continue to cultivate information technology."[31]

Article seven addressed education for those aged six to xvi, in order, as the treaty states, to "insure the civilization of the Indians entering into this treaty".[30] : 5 [31] The tribes agreed to hogtie both male and females to attend school, and the authorities agreed to provide a school and instructor for every xxx students who could be fabricated to attend.[31]

In article eight, the regime agreed to provide seeds, tools, and training for any of the residents who selected tracts of country, and agreed to farm them. This was to be in the corporeality of upwardly to $100 dollars worth for the first yr, and upwardly to $25 worth for the second and tertiary years.[31] These were i of a number of provisions of the treaty designed to encourage farming, rather than hunting, and move the tribes "closer to the white man'southward way of life."[44] : 44

Later ten years the government may withdraw the individuals from commodity 13, just if so, will provide $x,000 annually "devoted to the instruction of said Indians ... every bit will best promote the educational activity and moral comeback of said tribes." These are to be managed by a local Indian agent nether the Commissioner of Indian Affairs.[31] [45]

Article 10 provided for an resource allotment of wearing apparel, and food, in addition to one "good American cow" and two oxen for each lodge or family unit who moved to the reservation.[30] : 5 [31] It further provided for an annual payment over 30 years of $ten for each person who hunted, and $20 for those who farmed, to be used past the Secretary of the Interior for the "purchase of such articles as from time to time the condition and necessities of the Indians may signal to be proper."[31]

Article 11 [edit]

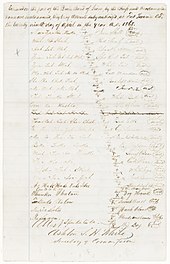

One of the signature pages from the treaty, including X marks for the tribal leaders, as a substitute for signed names

Article 11 included several provisions stating the tribes agreed to withdraw opposition to the construction of railroads (mentioned three times), armed services posts and roads, and volition non attack or capture white settlers or their property. The same guarantee protected 3rd parties divers as "persons friendly" with the United states.[7] : 1002 The regime agreed to reimburse the tribes for damages acquired in the construction of works on the reservation, in the amount assessed by "iii disinterested commissioners" appointed by the President.[31] It guaranteed the tribes access to the surface area to the north and due west of the Black Hills[thou] as hunting grounds, "then long every bit the buffalo may range thereon in such numbers as to justify the hunt."[46] : four

Every bit 1 source examined the treaty linguistic communication with regard to "and then long as the buffalo may range", the tribes considered this language to be a perpetual guarantee, because "they could non envision a day when buffalo would non roam the plains"; however:

The concept was clear enough to the commissioners … [who] well knew that hibernate hunters, with Sherman'due south blessing, were already offset the slaughter that would eventually drive the Indians to complete dependence on the government for their existence.[1]

Despite Sioux promises of undisturbed construction of railroads and no attacks, more than 10 surveying crew members, US Ground forces Indian scouts and soldiers were killed in 1872[27] : 49 [47] : 11, 13–4 [48] : 61 and 1873.[49] : 532–four [l]

Because of the Sioux massacre on the Pawnee in southern Nebraska during a hunting expedition in 1873, the U.s. banned such hunts exterior the reservation. Thus, the Us decision nullified a part of Article 11.[50] : eight

Article XII [edit]

Article 12 required the agreement of "three-fourths of all the adult male person Indians" for a treaty with the tribes to "be of whatever validity".[31] [32] : 44 Hedren reflected on commodity 12 writing that the provision indicated the government "already anticipated a time when different needs would demand the abrogation of the treaty terms."[30] : 5 These provisions have since been controversial, because subsequent treaties amending that of 1868 did not include the required understanding of three-fourths of developed males, so nether the terms of 1868, are invalid.[40] : 2 [m]

Manufactures Thirteen through XV [edit]

The government agreed to replenish the tribes with a "medico, teachers, carpenter, miller, engineer, farmer, and blacksmiths".[31] [45]

The government agreed to provide $100 in prizes for those who "in the judgment of the agent may grow the most valuable crops for the respective yr."[31] Once the promised buildings were constructed, the tribes agreed to regard the reservation every bit their "permanent home" and brand "no permanent settlement elsewhere".[31]

Article XVI [edit]

Fort Laramie Treaty (1851). Definition of Crow territory w of Powder River enlarged

Article 16 stated that country north of the North Platte River and due east of the summits of the Big Horn Mountains would exist "unceded Indian territory" that no white settlers could occupy without the consent of the tribes.[2] This included 33,000,000 acres (13,000,000 ha) of country exterior the reservation which were previously prepare aside past the 1851 treaty, too equally effectually an additional 25,000,000 acres (10,000,000 ha).[52] : 268 As role of this, the authorities agreed to close the forts associated with the Bozeman Trail. Article 16 did non however, accost issues related to important hunting grounds due north and northwest of the reservation.[30] : five The Arikara, Hidatsa and Mandan held the treaty correct to the bigger part of those hunting grounds co-ordinate to the 1851 treaty.[n] [7] : 594 [12] : map facing p. 112 With the 1868 treaty, the Sioux ceded land to the US directly north of the reservation.[o]

This article proclaims the shift of the Indian title to the land eastward of the summits of the Big Horn Mountains to Powder River (the combat zone of Reddish Cloud's War). In 1851, the The states had acknowledged the merits of the Crow to this expanse.[vii] : 595 Post-obit defeat, the Peace Commission recognized information technology as "unceded Indian territory" held by the Sioux. The Us Government could only dispose of Crow treaty territory, because information technology held parallel negotiations with the Crow tribe. The talks ended on May vii, 1868.[8] : 92 The Crows accepted to give up large tracts of land to the United states[p] and settle on a reservation in the middle of the 1851 territory.[q] [7] : 1008–1011 [8] : 99

Information technology was possible for the Peace Committee to permit the Sioux to hunt on the Republican Fork in Nebraska (200 miles south of the Sioux reservation) forth with others, considering the US held the title to this river area. The Cheyenne and Arapaho had ceded the western part of the Republican Fork in 1861 in a more-or-less well-understood treaty.[53] : 48 [54] The US had bought the eastern function of the Republican Fork from the Pawnee in 1833. The Pawnee held a treaty correct to hunt in their ceded territory.[7] : 416 [38] : 84 In 1873, the Massacre Canyon boxing took place here.[r]

Article XVII [edit]

The treaty, as agreed to "shall be construed every bit abrogating and annulling all treaties and agreements heretofore entered into."[31]

Signing [edit]

Over the course of 192 days catastrophe November 6, the treaty was signed by a total of 156 Sioux, and 25 Arapaho, in add-on to the commissioners, and an additional 34 signatories every bit witnesses.[55] Although the commissioners signed the document on April 29 along with the Brulé, the party bankrupt up in May, with simply 2 remaining at Fort Laramie to conclude talks at that place, before traveling upward the Missouri River to get together additional signatures from tribes elsewhere.[44] : 44 Throughout this procedure, no further amendments were made to the terms. As one writer phrased it, "the commissioners substantially cycled Sioux in and out of Fort Laramie ... seeking only the formality of the chiefs' marks and forgoing true agreement in the spirit that the Indians understood it."[33] : 2537–eight

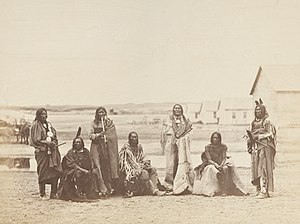

Sioux Chiefs (left) and members of the Peace Commission (right) at Fort Laramie, 1868

Post-obit initial negotiations, those from the Peace Committee did not talk over the conditions of the treaty to subsequent tribes who arrived over the following months to sign. Rather, the treaty was read aloud, and information technology was permitted "some time for the chiefs to speak" before "instructing them to place their marks on the prepared document."[44] : 44 As the source continues:

These tribes had picayune interest in or understanding of what had taken place at the Fort Laramie councils. They wanted the whites out of their state and would fight equally long as necessary.[44] : 44

The procedure of abandoning the forts associated with the Bozeman Trail, every bit part of the conditions agreed to, proved to be a long procedure, and was stalled by difficulty arranging the auction of the goods from the fort to the Bureau of Indian Affairs. Fort C.F. Smith was not emptied until July 29. Fort Phil Kearny and Fort Reno were not emptied until August 1. In one case abandoned, Red Cloud and his followers, who had been monitoring the activities of the troops rode down and burned what remained.[44] : 45–6

The peace commission dissolved on October 10 afterward presenting its study to Congress, which amid other things, recommended the government "finish to recognize the Indian tribes as domestic dependent nations," and that no further "treaties shall exist made with any Indian tribe."[44] : 46 William Dye, the commander at Fort Laramie was left to stand for the commission, and met with Red Cloud, who was among the last to sign the treaty on November 6.[30] : 3 [44] : 46 The government remained unwilling to negotiate the terms further, and later ii days, Cherry-red Deject is reported to have "washed his hands with the dust of the floor" and signed, formally ending the war.[44] : 46

The US Senate ratified the treaty on Feb sixteen, 1869.[56] : 1

Signatories [edit]

Notable signatories presented in the order they signed are as follows. Two exceptions are included. Henderson was a commissioner, but did non sign the treaty. Red Deject was among the terminal to sign, simply is listed here out-of-guild forth with the other Oglala.

Commissioners [edit]

- Nathaniel Green Taylor, Commissioner of Indian Affairs[31]

- William Tecumseh Sherman, lieutenant full general, United states of america Army[31] [s]

- William S. Harney, Brevet major full general, US Army[31]

- John B. Sanborn, former brevet major full general of volunteers, and former member of a previous peace commission organized by Alfred Sully[i]

- Samuel F. Tappan, journalist, abolitionist, and activist who rose to prominence afterward investigating the Sand Creek massacre[1]

- Christopher C. Diviner, Brevet Major General, and commander of the Department of the Platte[one] [t]

- Alfred Terry, Brevet major general, The states Regular army[31]

- John B. Henderson, United states Senator and Chairman of the Usa Senate Committee on Indian Affairs[57] [u]

Chiefs and headmen [edit]

Aftermath and legacy [edit]

Although the treaty required the consent of 3-fourths of the men of the tribes, many did not sign or recognize the results.[4] Others would later complain that the treaty contained circuitous linguistic communication that was not well explained in order to avert arousing suspicion.[xl] : 1–ii Yet others would not fully learn the terms of the understanding until 1870, when Ruby Cloud returned from a trip to Washington D.C.[44] : 47

The treaty overall, and in comparing with the 1851 agreement, represented a departure from before considerations of tribal customs, and demonstrated instead the government's "more heavy-handed position with regard to tribal nations, and ... want to digest the Sioux into American belongings arrangements and social customs."[60]

According to i source, "animosities over the treaty arose well-nigh immediately" when a grouping of Miniconjou were informed they were no longer welcome to trade at Fort Laramie, being south of their newly established territory. This was withal that the treaty did not make any stipulation that the tribes could not travel exterior their land, only that they would not permanently occupy exterior state. The only travel expressly forbidden by the treaty was that of white settlers onto the reservation.[one]

Although a treaty between the The states and the Sioux, it had profound effect on the Crow tribe, since information technology held the title to some of the territories ready bated in the new treaty. By entering the peace talks "... the authorities had in effect betrayed the Crows, who had willingly helped the army to hold the [Bozeman Trail] posts ...".[27] : 40

When the Sioux Indians had stopped the advance of the US in 1868, they quickly resumed their "own program of expansions"[21] : 342 into the adjoining Indian territories.[12] : 120 Although all parties took and gave,[6] : 145–6 [18] : 135–6 [61] : 42 the Sioux and their allies one time once more threatened the homeland of some of the Indian nations around them. Attacks on the Crows and the Shoshones were "frequent, both by the Northern Cheyennes and by the Arapahos, as well equally the Sioux, and by parties made up from all iii tribes".[62] : 347 [63] : 127, 153, 257 The Crows reported Sioux Indians in the Bighorn area from 1871.[61] : 43 This eastern part of the Crow reservation was taken over a few years later by the Sioux in quest of buffalo. When a force of Sioux warriors confronted a Crow reservation camp at Pryor Creek in 1873 throughout a whole day,[8] : 107 Crow primary Blackfoot called for decisive actions against the Indian intruders by the US.[8] : 106 In 1876, the Crows (and the Eastern Shoshones) fought alongside the Ground forces at the Rosebud.[8] : 108–9 [27] : 114–six They scouted for Custer against the Sioux, "who were at present in the old Crow country".[64] : X

Both the tribes and the government chose to ignore portions of the treaty, or to "comply only as long as conditions met their favor," and between 1869 and 1876, at least seven carve up skirmishes occurred within the vicinity of Fort Laramie.[30] : vi–7 Prior to the Black Hills expedition, Army sources mention attacks in Montana north of the Yellowstone and n of the Sioux reservation in North Dakota carried out by unidentified groups of Sioux.[48] : 61, 66 Large war parties of Sioux Indians left their reservation to set on afar Indian enemies most Like-a-Fishhook Village.[12] : 120 [xviii] : 133 [65] : 112 [x] The first talks of actions against the Sioux arose. In his 1873 written report, the Commissioner of Indian Diplomacy advocated, "that those [Sioux] Indians roaming westward of the Dakota line be forced by the military to come in to the Nifty Sioux Reservation."[66] : 145

The authorities eventually bankrupt the terms of the treaty post-obit the Black Hills Gold Rush and an expedition into the area past George Armstrong Custer in 1874, and failed to prevent white settlers from moving onto tribal lands. Rising tensions eventually led again to open up conflict in the Great Sioux War of 1876.[9] [32] : 46 [67]

The 1868 treaty would be modified three times by the US Congress between 1876 and 1889, each time taking more land originally granted, including unilaterally seizing the Blackness Hills in 1877.[60]

United states of america five. Sioux Nation of Indians [edit]

On June 30, 1980, the US Supreme Court ruled that the government had illegally taken land in the Black Hills granted by the 1868 treaty, past unlawfully abrogating commodity ii of the agreement during negotiations in 1876, while declining to accomplish the signatures of 2-thirds the adult male population required to practise so. It upheld an award of $15.v million for the market place value of the state in 1877, along with 103 years worth of interest at 5 percent, for an additional $105 million. The Lakota Sioux, nonetheless, have refused to accept payment and instead continue to demand the return of the territory from the United States.[68] As of 24 Baronial 2011[update] the Sioux involvement on the money has compounded to over 1 billion dollars.[69]

Commemoration [edit]

Marker the 150th anniversary of the treaty, the S Dakota Legislature passed Senate Resolution 1, reaffirming the legitimacy of the treaty, and co-ordinate to the original text, illustrating to the federal regime that the Sioux are "nevertheless here" and are "seeking a future of forward-looking, positive relationships with full respect for the sovereign status of Native American nations confirmed by the treaty."[70] [71]

On March 11, 2018, the Governor of Wyoming, Matt Mead signed a similar bill into law, calling on "the federal government to uphold its federal trust responsibilities," and calling for a permanent display of the original treaty, on file with the National Archives and Records Administration, in the Wyoming Legislature.[72] [73]

Run across as well [edit]

- Black Hills Land Claim, ongoing dispute between the Sioux and the The states Government

- Dakota Admission Pipeline, hush-hush oil pipeline, opposed by some Sioux based on the terms of the 1851 and 1868 treaties

- Indian Appropriations Deed, series of legislation passed by the US government related to tribal lands

- Listing of U.s. treaties, articles on treaties to which the US was a party

- Medicine Gild Treaty – Negotiated past the Peace Committee with southern Plains Indian tribes in 1867

Notes [edit]

- ^ Iron Crush was the showtime to sign the certificate on April 29. Scarlet Cloud and five others were the concluding on November half dozen.[1]

- ^ officially the Treaty with the Sioux–Brulé, Oglala, Miniconjou, Yanktonai, Hunkpapa, Sans Arcs, and Santee–and Arapaho, 1868 [2]

- ^ depending on the estimation of commodity Sixteen

- ^ called Gros Ventre

- ^ See Map 2

- ^ see Map 3

- ^ Run into Map 1, light-green area 529 and grey expanse 620

- ^ map facing p. 112[12]

- ^ Meet Map 1, yellowish area 571, grey surface area 619 and pink area 635

- ^ See Map 1, pocket-size pink area 472 in the lower right side

- ^ Modern day Wyoming and Montana

- ^ See Battle of Honsinger Bluff and Battle of Pease Bottom.

- ^ In the example of the 1876 proposal to relinquish the territory of the Black Hills, the document was signed by but ten% of adult males. Congress none-the-less passed an act in 1877 enacting the terms.[51]

- ^ Run across Map 1, light-green surface area 529 and greyness area 620

- ^ Map i. Yellow area 516

- ^ Run into Map 1, yellow area 517 ceded

- ^ See Map one, gray expanse 619 and pinkish area 635

- ^ See Map 3

- ^ Sherman was recalled to Washington D.C. in the previous November.[1] Co-ordinate to one source, he "would come up and go throughout he life of the committee."[44] : 39 Co-ordinate to the aforementioned source, Sherman was likewise recalled to Washington D.C. the following April to testify in the Impeachment of Andrew Johnson.[44] : 42–3

- ^ Augur replaced Sherman equally commissioner when Sherman was recalled.[44] : 39

- ^ Henderson is listed in the offset paragraph of the treaty as a party, but dissimilar the remaining commissioners, his signature does not appear in the original document following the text of the treaty. Compare also this extract from the original document from the National Archives and Records Assistants. According to one source, the previous November, both Sherman and Henderson were recalled to Washington D.C. "to attend urgent business."[1] Effectually October, one source has Henderson in Washington attention to the impeachment proceedings of President Andrew Johnson.

- ^ Some sources announced to disputed this[4]Although Sitting Bull was a member of the Hunkpapa Lakota,[58] his signature is listed on the treaty itself under "the Ogallalla band of Sioux by the chiefs and headmen whose names are hereto subscribed". Whether this may be attributable to fault on the office of those who crafted the treaty or those bearing witness and recording the signatures is unclear.

- ^ Red Cloud was among the terminal to sign the treaty, insisting he look until the army had cleared forts along the Bozeman Trail as they had agreed to. He supposedly replied to attempts to bring him to the talks "We are on the mountains looking downward on the soldiers and forts. When nosotros see the soldiers moving away and the forts abandoned, so I will come down and talk."[30] : 3 His inflow at the fort is variously reported as both November 4[1] and October 4,[30] : 3 although both agree he signed the treaty on November 6.[1]

- ^ See Map 1, grey expanse 620 and a part of the bordering pink area

References [edit]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j McChristian, Douglas C. (March 13, 2017). Fort Laramie: Military Bastion of the High Plains. University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN9780806158594 . Retrieved April 23, 2018.

- ^ a b c d Robinson, Three, Charles M. (September 12, 2012). A Good Year to Die: The Story of the Bully Sioux War. Random mansion Publishing Group. ISBN9780307823373 . Retrieved April 23, 2018.

- ^ Brownish, Dee (1970). "xv. Standing Bear Becomes a Person". Bury My Heart at Wounded Human knee. United States: St. Martin'south Press. p. 352. ISBN978-0-8050-6669-2.

Ten years later, however—while the treaty makers were negotiating with the Sioux—through some bureaucratic blunder in Washington the Ponca lands were included with territory assigned the Sioux in the treaty of 1868. Although the Poncas protested over and again to Washington, officials took no action. Wild young men from the Sioux tribes came down demanding horses as tribute, threatening to drive the Poncas off land which they now claimed as their own.

- ^ a b c d e "Section iii: The Treaties of Fort Laramie, 1851 & 1868". Due north Dakota Studies, N Dakota Land Government . Retrieved March ix, 2018.

- ^ a b c "Fort Laramie Treaty of 1851 (Horse Creek Treaty)" (PDF). National Park Service. Archived from the original on March 10, 2018. Retrieved June 11, 2018.

- ^ a b Gerrick, Mallory (1880). "The Dakota Winter Counts". Almanac report of the Bureau of Ethnology to the Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution 4th 1882–1883. Smithsonian Institution, Bureau of American Ethnology. pp. 89–127. OCLC 855931398. Retrieved Apr 27, 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f m h i j k Kappler, Charles J. (1904). Indian Affairs. Laws and Treaties. Vol. 2 . U.s. Government Publishing Office. OCLC 33039737. Retrieved April 24, 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Hoxie, Frederick E (1995). Parading Through History: The Making of the Crow Nation in America 1805–1935. Cambridge University Press. ISBN9780521485227 . Retrieved April 24, 2018.

- ^ a b c "Wyoming: Fort Laramie National Historic Site". National Park Service. Archived from the original on March ten, 2018. Retrieved March ix, 2018.

- ^ a b Stands In Timber, John; Freedom, Margot; Utley, Robert Marshall (1998). Cheyenne Memories. Yale Academy Press. ISBN9780300073003 . Retrieved Apr 24, 2018.

- ^ Kennedy, Michael (1961): The Assiniboine. Norman.

- ^ a b c d due east f g h Meyer, Roy Willard (October 1, 1977). The hamlet Indians of the upper Missouri: the Mandans, Hidatsas, and Arikaras. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN9780803209138 . Retrieved April 25, 2018.

- ^ a b Malouf, Carling Isaac (1963). Crow-Flies-High (32MZ1), a Historic Hidatsa Village in the Garrison Reservoir Area, North Dakota. United states of america Regime Publishing Office. OCLC 911830143. Retrieved April 25, 2018.

- ^ a b Medicine Crow, Joseph (1992). From the Heart of the Crow Land: The Crow Indians' Own Stories. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN080328263X . Retrieved Apr 25, 2018.

- ^ Schneider, Mary J.; Schneider, Carolyn (1987). The way to independence: memories of a Hidatsa Indian family unit, 1840–1920. Minnesota Historical Society Printing. ISBN9780873512183 . Retrieved April 25, 2018.

- ^ Mallery, Garrick (1972). Moving-picture show-writing of the American Indians. Courier Corporation. ISBN9780486228426.

- ^ Greene, Candace (May 4, 2015). "Verbal Meets Visual: Sitting Bull and the Representation of History". Ethnohistory. 62 (2): 217–40. doi:x.1215/00141801-2854291.

- ^ a b c d McGinnis, Anthony (1990). Counting Coup and Cutting Horses: Intertribal Warfare on the Northern Plains, 1738-1889. Cordillera Printing. ISBN9780917895296 . Retrieved April 25, 2018.

- ^ a b Allen, Charles Wesley; Red Cloud; Sam Deon (1997). Autobiography of Cerise Cloud: War Leader of the Oglalas . Montana Historical Society. ISBN9780917298509 . Retrieved April 25, 2018.

- ^ Serial 1220, 38th Congress, 2nd Session, Vol. 5, House Executive Document No. 1.

- ^ a b White, Richard (September 1978). "The Winning of the West: The Expansion of the Western Sioux in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries". The Journal of American History. 65 (2): 319–343. doi:10.2307/1894083. JSTOR 1894083. OCLC 6911158355.

- ^ Series 1308, 40th Congress, 1st Session, Vol. 1, Senate Executive Document No. 13.

- ^ Ostlind, Emilene (November viii, 2014). "Cerise Cloud'southward War". Wyoming State Historical Society. Archived from the original on February 24, 2018. Retrieved March nine, 2018.

- ^ Ewers, John Canfield (1975). Intertribal Warfare as the Precursor of Indian-white Warfare on the Northern Great Plains. Western History Clan. pp. 397–410. ASIN B0007C7DAQ. OCLC 41759776. Retrieved April 23, 2018.

- ^ Calloway, Colin G. (January 16, 2009). "The Inter-tribal Residual of Power on the Bang-up Plains, 1760–1850". Journal of American Studies. xvi (1): 25–47. doi:10.1017/S0021875800009464. JSTOR 27554087. S2CID 145143093.

- ^ Utley, Robert Thou.: "The Bozeman Trail before John Bozeman: A Decorated Land." Montana, the Mag of Western History. Vo. 53 (Sommer 2003), No. ii, pp. 20-31.

- ^ a b c d Dunlay, Thomas W. (1982). Wolves for the Blue Soldiers: Indian Scouts and Auxiliaries With the United States Regular army, 1860–90 . University of Nebraska Press. ISBN9780803216587 . Retrieved April 25, 2018.

- ^ a b Papers Relating to Talks and Councils Held with the Indians in Dakota and Montana Territories in the Years 1866-1869. United States Authorities Publishing Part. 1910. OCLC 11618252. Retrieved April 27, 2018.

- ^ a b "Sioux Treaty of 1868". National Archives and Records Administration. August 15, 2016. Retrieved March 8, 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f m h i j k l Hedren, Paul L. (1988). Fort Laramie and the Bang-up Sioux State of war. University of Oklahoma Printing. ISBN9780806130491 . Retrieved April 27, 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k fifty chiliad n o p q r s t u v w x y "Fort Laramie Treaty, 1868". Avalon Project . Retrieved March 9, 2018.

- ^ a b c d Viegas, Jennifer (2006). The Fort Laramie Treaty, 1868: A Master Source Examination of the Treaty that Established a Sioux Reservation in the Black Hills of Dakota. The Rosen Publishing Group. ISBN9781404204386 . Retrieved Apr 27, 2018.

- ^ a b "A Bad Man is Hard to Find" (PDF). Harvard Constabulary Review. 127. June 20, 2014. OCLC 5603885161. Retrieved March 15, 2018.

- ^ a b Blaine, Garland James; Blaine, Martha Royce (1977). "Pa-Re-Su A-Ri-Ra-Ke: The Hunters That Were Massacred" (PDF). Nebraska History. 58: 342–358. Retrieved Apr 27, 2018.

- ^ Standing Bear, Luther (1975) [First published 1928]. My People, the Sioux . University of Nebraska Press. ISBN9780803293328 . Retrieved April 25, 2018.

- ^ Standing Bear, Luther (November 1, 2006). State of the Spotted Hawkeye . Academy of Nebraska Press. ISBN9780803293335 . Retrieved April 25, 2018.

- ^ Riley, Paul D. (1973). "The Battle of Massacre Canyon" (PDF). Nebraska History. 54: 220–249. Retrieved April 27, 2018.

- ^ a b Blaine, Martha Royce (1990). Pawnee Passage, 1870–1875 . University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN9780806123004 . Retrieved April 25, 2018.

- ^ "Indian Office Documents on Sioux-Pawnee Battle." Nebraska History. Vol. sixteen (1935), No. 3, pp. 147-155.

- ^ a b c Bell, Robert A. (2018). "The Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868 and the Sioux: Is the United States Honoring the Agreements information technology Made?". Indigenous Policy Journal. 28 (3). Retrieved March 9, 2018.

- ^ "A Century of Lawmaking for a New Nation: US Congressional Documents and Debates, 1774–1875 U. S. Serial Set, Number 4015". Library of Congress. United states of america Authorities Publishing Office. December xxx, 1901. Retrieved April 25, 2018.

- ^ Howard, James Henri (1995) [Originally published: Washington: U.S. Govt. Print. Off., 1965]. The Ponca Tribe. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN9780803272798 . Retrieved April 27, 2018.

- ^ a b Report – United States, Agency of Indian Affairs, Planning Support Group, Outcome 267. U.s.a. Bureau of Indian Diplomacy. 1876. Retrieved March ix, 2018.

- ^ a b c d eastward f g h i j g l Oman, Kerry R. (2002). "The Beginning Of The End The Indian Peace Commission Of 1867~1868". Dandy Plains Quarterly. 2323. OCLC 864704686. Retrieved March fourteen, 2018.

- ^ a b "1868: Fort Laramie Treaty promises to provide health intendance, services". United States National Library of Medicine . Retrieved March ix, 2018.

- ^ Hollabaugh, Mark (June 2017). The Spirit and the Sky: Lakota Visions of the Cosmos. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN9781496200402 . Retrieved April 27, 2018.

- ^ Robertson, Francis B. (1984). ""Nosotros Are Going to Have a Big Sioux War": Colonel David S. Stanley'southward Yellowstone Expedition, 1872". Montana: The Magazine of Western History. 34 (4): 2–fifteen. JSTOR 4518849.

- ^ a b Webb, George West. (1939). Chronological List Of Engagements Between The Regular Army Of The United States And Various Tribes Of Hostile Indians Which Occurred During The Years 1790 And 1898, Inclusive' . Fly Printing and Publishing Visitor. OCLC 654443885. Retrieved April 25, 2018.

- ^ Howe, George Frederick (December 1952). "Expedition to the Yellowstone River in 1873: Letters of a Young Cavalry Officeholder". The Mississippi Valley Historical Review. 39 (3): 519–534. doi:10.2307/1895008. JSTOR 1895008.

- ^ Annual Report of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, 1873. United States Authorities Publishing Office. 1874. OCLC 232304708. Retrieved April 27, 2018.

- ^ "United states v. Sioux Nation of Indians, 448 U.s. 371 (1980)". Justia . Retrieved March 15, 2018.

- ^ Lazarus, Edward (1999). Black Hills White Justice: The Sioux Nation Versus the U.s.a., 1775 to the Present. University of Nebraska Printing. ISBN9780803279872.

- ^ Weist, Tom (1984): A History of the Cheyenne People. Billings.

- ^ Serial 4015, 56th Congress, 1st Session, pp. 824–825.

- ^ "Fort Laramie, 1868". Lakota County Times. Middle for American Indian Research and Native Studies. May 4, 2017. Retrieved March 14, 2018.

- ^ Congressional Edition, Written report No. 77, Claims of Sioux Tribe of Indians Earlier Courtroom of Claims. The states Authorities Publishing Office. 1919. Retrieved April 27, 2018.

- ^ "150th Anniversary – Treaty of Fort Laramie Exhibition". Brinton Museum . Retrieved March 13, 2018.

- ^ "Sitting Bull". PBS, New Perspectives on the West . Retrieved October 1, 2018.

- ^ "Our Documents – Transcript of Treaty of Fort Laramie (1868)". Apr 9, 2021.

- ^ a b Matson, Laura (2017). "Treaties & Territory: Resource Struggles and the Legal Foundations of the U.s.a./American Indian Relationship". Open Rivers: Rethinking The Mississippi. Academy of Minnesota Libraries. Retrieved March 14, 2018.

- ^ a b Lubetkin, John Grand (2002). "The Forgotten Yellowstone Surveying Expeditions of 1871. W. Milnor Roberts and the Northern Pacific Railroad in Montana". Montana The Magazine of Western History. 52 (4). OCLC 367823756. ProQuest 217971348.

- ^ Bent, George; Hyde, George Due east. (1968). Life of George Bent Written from His Messages. Academy of Oklahoma Printing. ISBN9780806115771 . Retrieved Apr 25, 2018.

- ^ Linderman, Frank B. (1962). Enough Coups. Chief of the Crows. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN9780803280182 . Retrieved April 25, 2018.

- ^ Medicine Crow, Joseph (1939). The Effects of European Culture Contacts Upon the Economic, Social, and Religious Life of the Crow Indians. Academy of Southern California. OCLC 42984003. Retrieved April 25, 2018.

- ^ Howard, James H. (1960). "Butterfly's Mandan Winter Count: 1833–1876". Ethnohistory. vii (one): 28–43. doi:10.2307/480740. JSTOR 480740.

- ^ Kvasnicka, Robert Chiliad.; Viola, Herman J. (1979). The Commissioners of Indian Affairs, 1824–1977. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN9780803227002 . Retrieved April 27, 2018.

- ^ "Black Hills Trek (1874)". Smithsonian Institution Athenaeum . Retrieved March 9, 2018.

- ^ Frommer, Frederic (Baronial nineteen, 2001). "Blackness Hills Are Beyond Price to Sioux". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original (Suggested Reading Black Elk Speaks and Articles Beneath) on November eleven, 2014. Retrieved December 28, 2013.

- ^ Streshinsky, Maria (February nine, 2011). "Saying No to $1 Billion". The Atlantic . Retrieved April 27, 2018.

- ^ "S.D. Senate Passes Resolution Confirming South Dakota's Support for the 1868 Treaty of Fort Laramie". South Dakota Autonomous Party. January 25, 2018. Retrieved March 14, 2018.

- ^ "Senate Resolution No. 1". State of South Dakota . Retrieved March 14, 2018.

- ^ "Wyoming Governor Signs 41 Bills into Police force". KGAB . Retrieved March 15, 2018.

- ^ "SJ0002 – 150th Anniversary of the 1868 Treaty of Fort Laramie". Wyoming Legislature . Retrieved March 15, 2018.

Further reading [edit]

- "Treaty with the Sioux — Brulé, Oglala, Miniconjou, Yanktonai, Hunkpapa, Blackfeet, Cuthead, Two Kettle, Sans Arcs, and Santee — and Arapaho, 1868" (Treaty of Fort Laramie, 1868). fifteen Stat. 635, Apr 29, 1868. Ratified Feb xvi, 1868; proclaimed February 24, 1868. In Charles J. Kappler, compiler and editor, Indian Diplomacy: Laws and Treaties — Vol. Ii: Treaties. Washington, D.C.: Regime Printing Office, 1904, pp. 998–1007. Through Oklahoma State University Library, Electronic Publishing Center...

- Harjo, Suzan Shown (2014). Nation to Nation: Treaties Betwixt the U.s.a. and American Indian Nations. Nation to Nation. National Museum of the American Indian. p. 127. ISBN9781588344786.

External links [edit]

- American Indian Rights And Treaties – The Story Of The 1868 Treaty Of Fort Laramie, video from Insider Sectional

- Fort Laramie Treaty: Case Study from the National Museum of the American Indian

- Collection of Photographs past Alexander Gardner, from his travels with the Peace Commission at Fort Laramie in 1868, from the Minnesota Historical Club

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Treaty_of_Fort_Laramie_%281868%29

0 Response to "Fort Laramie Treaty Art Xii 34th Adult Male Women"

Post a Comment